Corpus is Latin for “body”, as in Corpus Christi (“body of Christ”). In linguistics, however, it refers to a large collection of computer-readable texts (whether spoken or written) which can be searched and explored using computational methods. Corpus linguistics has grown in sophistication alongside the explosion of personal computing, as larger corpora (the Latin plural for “corpus”) have become available and new analytical tools are developed.

The corpus methodology developed as a response to a dominant trend in linguistics known as “arm-chair linguistics”, a tongue-in-cheek reference to relying on so-called “native-speaker intuition” for insights into linguistic acceptability or grammaticality. By collecting large databases of “used language” – speech and writing as they’re used in practice – linguists have been able to describe patterns of usage emerging from corpora that are often outside an individual speaker’s awareness.

Concordance and collocation

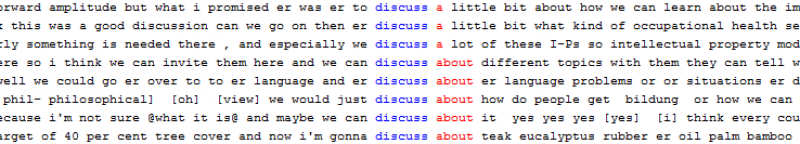

The basic tool of corpus research remains the concordancer – a piece of software that can open a collection of texts and produce concordance lines for a specific word. The header image of this blog is a set of concordance lines for the word discuss. This image is a screen capture from AntConc, a freely distributed concordancer tool and excellent way to start exploring corpora. Also known as KWIC view (Key Words In Context), concordance lines are a way to find recurring patterns in usage and meaning.

These patterns are also known as collocations, which refers to co-occurrence of a word with certain other words. Corpus tools like AntConc can also search for collocations and n-grams, which are recurring chunks of language of various size. For example, frequent bigrams (two-word chunks) in speech include of course, i mean, and yeah but. Longer chunks include 4-grams such as on the other hand. These patterns are so strong in used language that phraseology has become a major area of research. Many linguists are convinced that we store and retrieve these chunks of language as whole units, which supports the cognitive demands of speech as well as the perception of fluency.

Letting the data speak for itself

As a linguistic methodology based on language in use (as opposed to native-speaker intuition), corpus linguistics is well suited for ELF research. Rather than starting out with preconceived notions of what is “good” or “bad” English, a corpus methodology allows the data to speak for itself. One of the most promising areas for describing ELF is in its phraseology, as the patterns of usage emerging from this data are different from those found in native speakers who grow up in English-speaking communities.

Maybe you noticed that the concordance lines in the blog header contain an interesting pattern. The data is from the ELFA corpus, a one-million-word database of transcribed ELF speech from academic settings (130 hours in total). The data shows a pattern of “discuss about” something, which is perfectly intelligible (and likely not even noticed in the discussions), though this is not a native speaker preference. Who, then, is discussing about their subject?

Looking more closely at this pattern, it occurs 8 times in the ELFA corpus in 7 different speech events, uttered by native speakers of Finnish, Polish, and German. The pattern is even more widespread in the VOICE corpus, where it occurs 12 times in 11 events. Here the speakers’ first languages are German, Dutch, French, Greek, Lithuanian, Turkish, and Portuguese.

Thus, while this pattern is not dominant quantitatively (only 6% of the instances of discuss in VOICE employ this discuss about collocation), it is widely distributed across locations, types of speech, and different speakers, suggesting this is more than a mere “learner error”, first language “interference”, or some random idiosyncrasy. With time, ELF corpus research will take on a diachronic perspective, meaning corpora collected from different times will be compared to see if this feature might be a growing trend in ELF.

Until then, beware of researchers making grand, sweeping claims about “emerging trends” in ELF, especially when these claims are based on qualitative analysis of small, unrepresentative sets of data. ELF description has only just begun.