In folk traditions and traditional societies, an elf is one of several semi-corporeal entities often considered to be nature spirits or forest inhabitants who exist on a continuum of malevolence and benefaction toward human beings. As a society whose traditional beliefs survived well into the modern era, Finland’s forests are liberally populated with such entities, variously identified as haltija, näkki, Hiisi, Tuoni, and the power (väki) of water and stones.1

In linguistics, however, ELF stands for English as a Lingua Franca, a new (~15 years old) research paradigm that has drawn the interest of many applied linguists and English language teachers. It began as a response to the hegemony of English native speakers in these fields, and especially as a response to the changing role of English in today’s globalised world.

It has long been recognised that non-native speakers/users of English far outnumber its native speakers. Moreover, the rise of English as a lingua franca – a contact language between speakers who do not share a first language – has shifted scholarly interest away from the US/UK as “owners” of the English language. Rather than view ELF as “deficient” or “learner language” on a hopeless journey toward “native-like” mastery, ELF researchers treat the English used between its non-native speakers as a legitimate form of English that deserves to be studied and described in its own right.

Ideology vs. empirical research

The ELF field retains a strong ideological orientation, and much work remains to be done in “leveling the playing field”, especially for multilingual academics using English as a professional lingua franca. I’ve always found the ideological arguments in favor of ELF to be self-evident and uncontroversial; having no background in English language teaching (ELT), I sometimes wonder what all the fuss is about. Personally, I’m more intrigued by ELF data and the challenge of linguistic description.

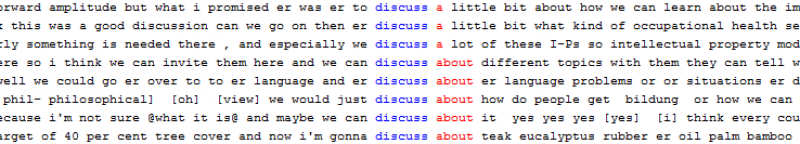

Descriptive ELF research remains in its infancy, although major databases of naturally occurring ELF data have been compiled and are beginning to be exploited. For empirical description of ELF with a solid corpus methodology (what’s a corpus?), see Anna Mauranen’s Exploring ELF: academic English shaped by non-native speakers (CUP, 2012). She compares two corpora of spoken academic English (ELFA and MICASE) and grounds the understanding of ELF in non-ideological, linguistically established fields of research.

For a more ideological treatment of ELF, I’ve found the first three chapters of Barbara Seidlhofer’s Understanding English as a Lingua Franca (OUP, 2011) to be a concise and persuasive overview of the need to reconceptualise English. She also discusses naturally occurring ELF data from the University of Vienna’s VOICE corpus, though her analysis is principally qualitative.

As a descriptively oriented ELF researcher, I think ELF as a field has overstated the value of its descriptive work, which should be seen as just beginning as it moves from qualitative analyses of tiny sets of data to quantitative analyses of meaningful corpora. The ideological concerns of the ELF paradigm have no shortage of advocates in the field, so I hope this blog will highlight the contributions of the Finnish school of ELF led by Prof. Anna Mauranen.

1 For a fascinating and readable overview of the Finnish folk religious tradition, its mythology, poetry, and historical roots, I highly recommend Anna-Leena Siikala’s Mythic Images and Shamanism: A Perspective on Kalevala Poetry (Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2002).